|

| The dedication of the Worth Monument, November 25, 1857; courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York |

This week, Tex-Mex restaurants and bars around the country will celebrate Cinco de Mayo, which many people wrongly think is Mexico's independence day. (That anniversary falls on September 16th). Cinco de Mayo

also has nothing to do with the Mexican-American War of 1846-48, another common misconception. (What Cinco de Mayo celebrates is the 1862 victory of the Mexicans over the French at the Battle of Puebla.)

New York does, however, have a strange and significant connection to that earlier conflict, and just two days after Cinco de Mayo is the anniversary of the death of General William Jenkins Worth, hero of the Battle of Chapultepec in the Mexican-American War and namesake of Fort Worth, Texas. While Worth died of cholera in Texas in 1849, his remains ended up in New York, a city in which he never lived while he was alive.

A protégé of Winfield (“Old Fuss and Feathers”) Scott, Worth fought in the War of 1812, the Seminole War in Florida, and the Mexican-American War. At the Battle of Chapultepec, Worth’s division took Mexico City’s San Cosme Gate, thus gaining access to the city in what would prove to be a decisive battle in the war. When Mexico City fell to the Americans, it was Worth himself who raised the American flag from the top of the National Palace.

(Though the Mexican-American War is often overlooked these days, it was a major turning point in American history, netting the United States the territories of Arizona, New Mexico, and California. And the Battle of Chapultepec—also known as the “Halls of Montezuma”—is still commemorated in the opening line of the

Marine Corps hymn.)

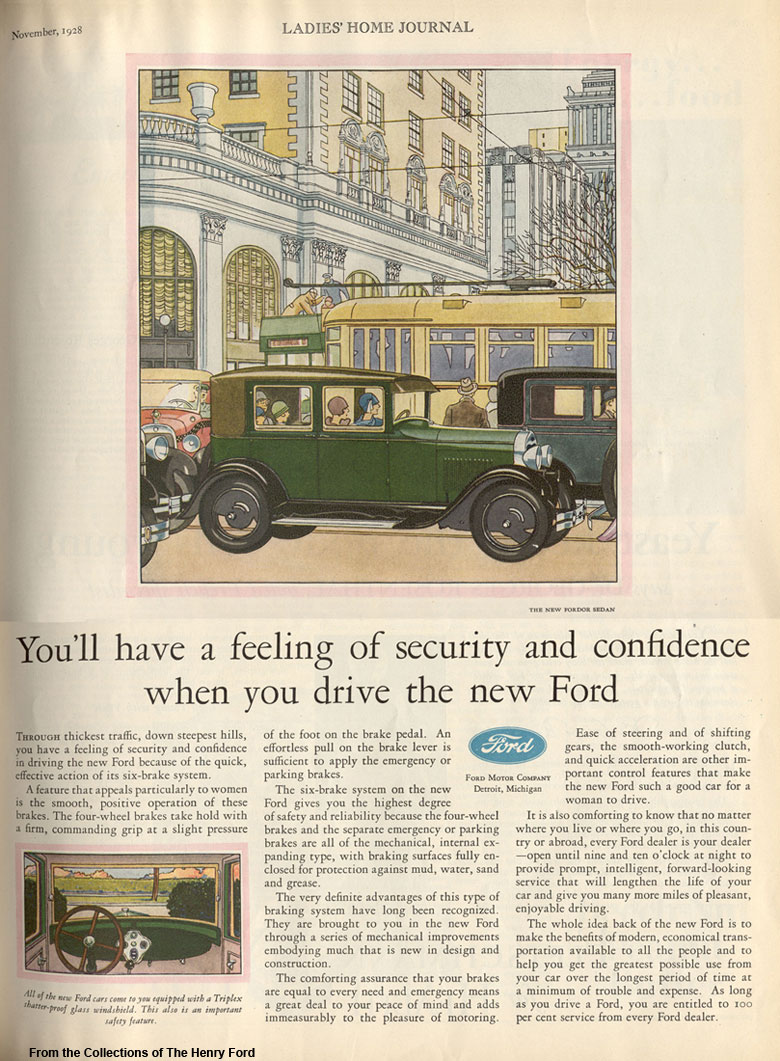

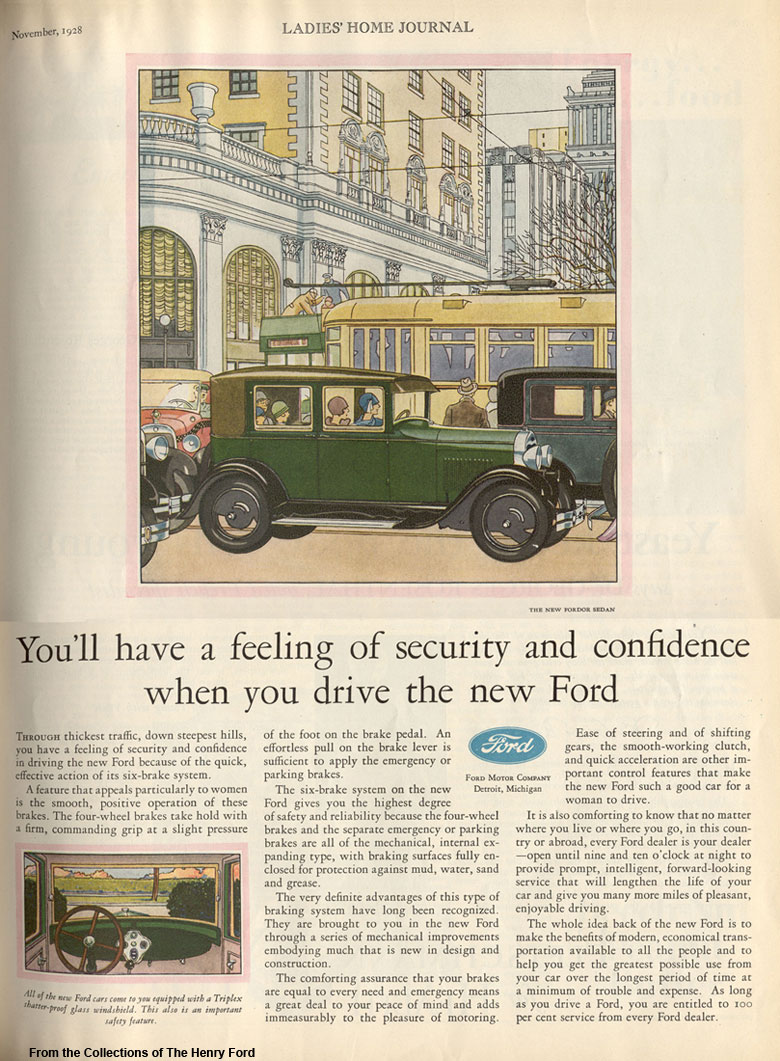

When Worth died in 1849, he was a famous man—but why he didn’t end up buried in Texas or in Hudson, New York (his childhood home) remains a bit of a mystery. Certainly, New York embraced him as a man deserving of all the pomp and circumstance it could muster. He was brought to the city and buried in a temporary tomb in Green-Wood cemetery while a proper monument could be erected at Madison Square. Once the monument was finished, Worth was reburied on November 25, 1857, in an elaborate ceremony after lying in state at City Hall. (November 25 was in those days an important holiday—

Evacuation Day—which marked the end of the American Revolution.)

Like an Egyptian pharaoh, Worth had numerous objects entombed with him, and they provide a fascinating insight into the customs of the time. Worth was a Mason and so many Masonic items were included, ranging from The Masonic Manual to a list of the lodges under the jurisdiction of the Grand Lodge in New York. Other items were particularly New York-centric and provide a time capsule of 1857; they include Valentine’s Manual, the constitution and by-laws of the Metropolitan Social Club, a catalogue of the New York Ophthalmic Hospital, and many documents pertaining to the building of Worth’s tomb. Added for good measure were newspaper stories covering George Washington’s funeral in 1799 and two pennies—perhaps on the general’s eyes—dating from 1787 and 1812.

The Worth Monument, which stands at the junction of Fifth Avenue and Broadway near the Flatiron Building, is one of only two stand-alone military gravesites of its kind in the city. (The other, grander structure is Grant’s Tomb in Riverside Park.)

But the tomb isn’t Worth’s only commemoration in New York. Running through Chinatown and Tribeca is Worth Street, which was named for him in the early 1850s. For many years that thoroughfare had been called Anthony Street and it was known as one of the worst streets in New York. Low-cost brothels clustered in the blocks of Anthony near the intersection of Orange and Cross Street. In 1829, the five-cornered intersection where Anthony, Orange, and Cross met had been dubbed “the Five Points,” and soon that name came to refer to the entire slum that radiated out from that hub.

By the 1850s, with a surge of poor Irish and German immigrants moving into Five Points, the city decided to improve the neighborhood’s fortunes through a little creative street renaming. If Anthony Street was terrible, they would literally wipe it off the map. In its place was Worth Street, named for the great hero of the war, and therefore free of any taint. (Around the same time, Orange Street was renamed Baxter in honor of Colonel Charles Baxter who had commanded the New York Regiment at Chapultepec and was killed. When Cross Street later became Park Street—now called Mosco Street—all three original street names that made up the infamous Five Points intersection were gone.)

[This blog post is adapted from an earlier version that ran on May 7, 2009.]

****

Read more about NYC history in