While most polls seem to indicate that Donald Trump isn't going to win the election today, if he were to win, he'd be only the second president born and bred in New York City. (The first was Teddy Roosevelt.)

[UPDATE: Well, the polls and pundits were wrong. Mr. Trump did win the election, becoming the second New Yorker to hold the nation's highest office.]

However, many presidents and vice presidents have had connections to the city over the years:

GEORGE WASHINGTON

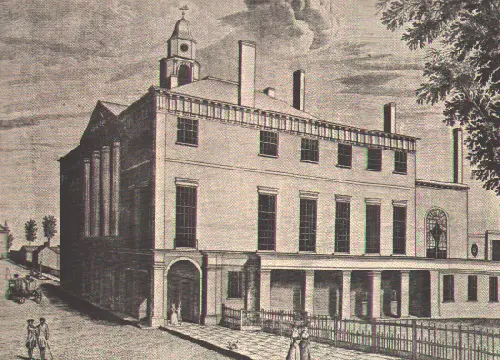

Though it didn't last very long, New York was the first capital of the United States, and on the balcony of Federal Hall on Wall Street, George Washington was sworn in as America's first president on April 30, 1789. (The building no longer stands, but a statue of Washington by J.Q.A. Ward graces the front of the building now known as Federal Hall National Memorial). After the inauguration, Washington went to St. Paul's Chapel on Broadway at Fulton Street, where his pew is still preserved. During the 15 months that New York remained the capital after the inauguration, Washington lived in a house on Cherry Street (at roughly the spot where the Brooklyn Bridge anchorage now stands) and then in a home on lower Broadway near Bowling Green. His vice president, John Adams, lived in isolated splendor in a mansion in Greenwich Village called Richmond Hill, later home to Vice President Aaron Burr.

AARON BURR

In 1800, the incumbent president, John Adams, was faced by his own vice president, Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson's running mate was New Yorker Aaron Burr; however, due to a flaw in the electoral system (which made no adequate provision for distinguishing between votes cast for president versus vice president), both Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr each received 73 electoral votes and the election was thrown to the House of Representatives. The Federalists, who still controlled congress, tried to elect Burr as president, thus denying the seat to Jefferson, who many considered the nation's leading opponent of Federalism. Notably, it was only though the intervention of Burr's nemesis,

Alexander Hamilton, that Jefferson was finally elected president on the 36th ballot. Burr's home in Greenwich Village, Richmond Hill, is no longer standing, but one of the property's stables is now the restaurant

One if By Land, Two if By Sea.

GEORGE CLINTON

GEORGE CLINTON

Aaron Burr was left off the Democratic-Republican ticket in 1804 in favor of New York governor George Clinton, who also went on to be James Madison's vice president (thus making him one of only two vice presidents to serve under different presidents; the other was the well-coiffed John C. Calhoun).

DEWITT CLINTON

In 1812, New York City fielded its first candidate for president, Mayor DeWitt Clinton. Despite mounting frustration with incumbent James Madison over the War of 1812, Clinton lost the election (had he won Pennsylvania, he would have reached the White House). Clinton went on to serve as New York's governor and presided over the building of the Erie Canal. (DeWitt Clinton is the person who is honored in the neighborhood Clinton—known to most people as Hell's Kitchen.)

DANIEL TOMPKINS

The man Clinton replaced as governor, Daniel Tompkins, was vice president under James Monroe. Tompkins, who gave the land to the city that became Tompkins Square Park, is buried in the churchyard at St. Marks in the Bowery on 10th Street at Second Avenue.

MARTIN VAN BUREN

In 1836, New York governor Martin Van Buren (who had been Andrew Jackson's secretary of state and vice president) was elected to the presidency. It would be the last time until George H.W. Bush that a sitting vice president would succeed to the presidency without the president dying in office. Another fun fact about Van Buren: not only was he a descendant of one of the early Dutch settlers of New York, he grew up speaking Dutch.

MILLARD FILLMORE

Generally forgotten in the lists of American presidents is Millard Fillmore, who hailed from the Finger Lakes region upstate. A congressman for over a decade in the 1830s and '40s, Fillmore returned to New York to run an unsuccessful campaign for governor. In 1848, he became the state's comptroller. In that capacity, he oversaw the start of construction on the state militia's arsenal in Central Park. Today, his name is still clearly visible in the plaque over the building's front door. In 1848, Fillmore was also tapped to be General Zachary Taylor's running mate. When Taylor died after only a year in office, Fillmore became president. However, like John Tyler before him (who had succeeded to the presidency upon the death of William Henry Harrison), Fillmore was not picked by his own party to run for a second term.

HORATIO SEYMOUR / HORACE GREELEY

In 1868, Governor Horatio Seymour (left) was tapped by the Democrats to face war hero Ulysses S. Grant. Seymour had long been involved in New York State politics—the factionalism of this period is sometimes hard to fathom. Seymour was a "soft-shell hunker," opposed to those in the party who were "hard-shell hunkers" or "barnburners." The hirsute Seymour sported an impressive neck-beard, which was quite the fashion of the time.

Newspaper editor Horace Greeley faced Grant in the election of 1872. Greeley, a staunch Republican, had become disillusioned by the party and Grant's mediocre first term and decided to face him as a "Liberal Republican." (The Democrats backed Greeley, as well.) Grant handily won a second term and Greeley died before the Electoral College could convene, meaning that his electoral votes were split between four other Democratic candidates.

A handsome statue of Greeley (who, like Seymour, sported a neck-beard—whatever happened to those?) sits in City Hall Park near the entrance of the Brooklyn Bridge.

SAMUEL J. TILDEN

Lawyer Samuel J. Tilden rose to prominence as the man who prosecuted William "Boss" Tweed. His success led to him winning the governor's race in 1874 and then being nominated for president by the Democratic Party in 1876 to face Ohio Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. The Tilden/Hayes election continues to be the most disputed in American history. It took four months from Election Day for a special commission to name the winner. Ultimately, they picked Hayes though modern research indicates that Tilden almost certainly would have won the election had there not been electoral shenanigans in Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana. Tilden lived in a wonderful double townhouse on Gramercy Park that is now home to

The National Arts Club.

CHESTER A. ARTHUR

Though a native of Vermont (or, as his opponents tried to prove in 1880, of

Canada), Chester A. Arthur moved to New York in 1854 to practice law. He was appointed collector of the Port of New York in 1871 and was nominated to run as James A. Garfield's vice president in 1880.

Garfield was shot in July 1881, only a few months after taking office. He lingered for eighty days before succumbing to his wounds. At the time of the president's death, Arthur was at his home on Lexington Avenue (

which still stands) and was sworn in as president there by a justice of the New York Supreme Court. He ran in 1885 to become president in his own right, but lost to New York Governor Grover Cleveland.

GROVER CLEVELAND

New York Governor Grover Cleveland was elected president in 1888 and again in 1892, the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms. (And the first Democrat to be nominated for president three consecutive times.) Cleveland's vice president during his second term was Adlai Stevenson, grandfather of the 20th-century presidential candidate who ran twice against Dwight D. Eisenhower.

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

New York City has only produced one born-and-raised president, Teddy Roosevelt, who grew up in a house on East 20th Street near Gramercy Park. (Today, the National Park Service runs the

Theodore Roosevelt birthplace in a replica house on the site.) Teddy became president in 1901 after President William

McKinley was

assassinated in Buffalo while attending the Pan-American Exposition. Roosevelt ran for election in his own right in 1904 and won, becoming the first vice president who had been elevated to the presidency who went on to win the office in his own right.

Teddy ran again in 1912 on the Progressive or "Bull Moose" ticket, siphoning enough votes away from incumbent Republican William Howard Taft to give the election to Woodrow Wilson.

AL SMITH

Lower East Sider Al Smith ("the Happy Warrior") rose to prominence in the state legislature in the early years of the 20th century. He was elected governor in 1918; though he lost the 1920 election, he was governor from 1922 to 1928 when he secured the Democratic nomination for president. The plainspoken Smith lost the election that year to Herbert Hoover, done in by a combination of prejudice (no Roman Catholic had ever sought the nation's highest office) and opposition to his "wet" candidacy during the height of Prohibition. Smith went on to be the head of the Empire State Corporation that erected the Empire State Building. His boyhood home, on Oliver Street, still stands and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT

FDR served longer than any other president, from 1937 to his death in 1945, thus ushering in the era of presidential term limits. (He faced New Yorker Wendell Willkie in the 1940 election and New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey in 1944.)

Born in

Hyde Park, New York, in 1882, Roosevelt was the descendant of two of the oldest New York families. His Delano ancestor, Philippe de La Noye, arrived in Plymouth, Massachusetts, on the

Fortune, the second ship to bring the Pilgrims to the New World. His Roosevelt ancestors had been in New York since the city had been New Amsterdam. Though he was only a distant cousin of Teddy Roosevelt, his wife, Eleanor, was Teddy's niece.

THOMAS E. DEWEY

Thomas Dewey was known as the "Gangbuster" for his crusades against bootlegging and organized crime as a New York City prosecutor and District Attorney. In 1942, he became governor and was nominated by the Republicans to face FDR in 1944 and then to face Harry Truman in 1948. Almost all pundits and pollsters considered Dewey's election a lock—so much so that the Chicago Daily Tribune went to bed on election night with "DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN" running across the page. In the end, though Truman only squeaked out a narrow popular victory, the margin in the Electoral College was overwhelming.

BARACK OBAMA