New York was only the capital of the United States for a brief time, but many important things happened during the city's tenure as the seat of government. Perhaps none is more central to our daily lives than the passage of the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution.

The Bill of Rights [warning: PDF], primarily written by future president James Madison, was designed to address what were seen as deficiencies in the Constitution, especially among anti-Federalists, who thought the original document ceded too much power to the federal government and didn't do enough to protect individual rights.

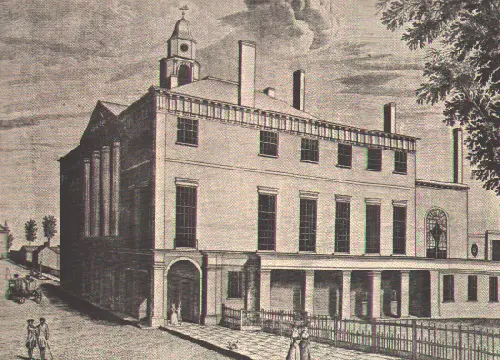

The House of Representatives, meeting in Federal Hall on Wall Street (pictured above), actually voted in favor of 17 amendments. Once the laws reached the Senate, they were combined and rewritten into 12 amendments, which then passed to the states for ratification. On December 15, 1791 -- 225 years ago today -- Virginia became the final state to agree to ten of those twelve amendments, putting the Bill of Rights into effect.

What became of the other two amendments passed along to the states?

One, which proposed a system for ensuring that the House of Representatives was never too small -- and that bolstered the power of less populous states -- couldn't garner the votes for passage.

The other amendment, regarding congressional pay raises -- first ratified by Maryland in 1789 -- was finally approved in 1992 and became the 27th Amendment, 201 years after the rest of the Bill of Rights became the law of the land.

Meanwhile, by the time the Bill of Rights had been ratified, Federal Hall was no long the seat of government. A deal between Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton at Jefferson's home on Maiden Lane moved the capital to Philadelphia in 1790 and, ultimately, to Washington DC. The Federal Hall pictured at the top was torn down in 1812 and today's Federal Hall National Memorial (originally the US Custom House, shown here under a blanket of snow during the blizzard of 1888) went up in 1842.