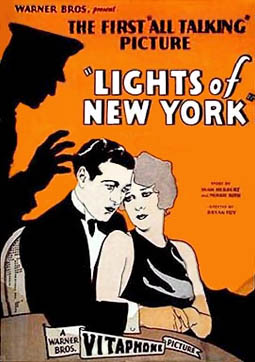

On July 26, 1928 -- eighty-two years ago today -- the first all-talking film, Lights of New York, opened across the country, ushering in the era of sound film and effectively killing the silent movie.*

The film had actually opened in New York at the Strand Theater** on July 6th to lukewarm critical reaction (The New York Times called it "crude in the extreme") but strong box office. Made for $23,000, the film ultimately grossed somewhere between $1.25 and $2 million dollars, thus proving that earlier sound films, like The Jazz Singer, weren't flukes. (Often billed as the first "talkie," The Jazz Singer has only two scenes of ad-libbed dialogue and the sound of Al Jolson singing; the rest of the film is essentially silent.)

The experimental nature of Lights of New York is apparent in its staging: boom mics were not in use, so stationery microphones were hidden throughout the set. The blocking in the film suffers, since characters could only speak when near a microphone, causing odd breaks in the dialogue as people walk from one microphone to another.

The film itself is a standard gangster movie: a rube from upstate comes to the city and ends up being the stooge for a Broadway speakeasy. However, the film had one notable line of dialogue: "Take him for a ride!" that went on to become a gangster cliche.

* By 1929, sound production was taking over and that year is

considered to be the last of the silent era though some directors -- notably

Charlie Chaplin -- would continue to make silent films well in the 1930s.

** The Strand is now gone; it stood on the site now occupied

by the Hershey's store at the northern end of Times Square.

by the Hershey's store at the northern end of Times Square.

To get RSS feeds from this blog, point your reader to this link.

To subscribe via email, follow this link.

Or follow us on Twitter.

.jpg)