| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

GET UPDATES IN YOUR INBOX! Subscribe to our SPAM-free updates here:

Showing posts with label Times Square. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Times Square. Show all posts

Thursday, October 4, 2018

Postcard Thursday: Reminder -- Sun Oct 7, Gilded Age Walking Tour

Thursday, July 20, 2017

Postcard Thursday: Apollo XI

On July 20, 1969, the Apollo XI capsule landed on the moon and humans walked on a celestial body for the first time.

A few days later, the Apollo astronauts--back on terra firma--were feted in New York with a major ticker tape parade. At the time, many claimed it was the largest ticker tape parade New York had ever seen, but as we were researching Inside the Apple, we found that same claim was made for many parades and it’s almost impossible to verify. (Four million people were said to have attended the Apollo parade—an impressive number, even if it’s not the largest.)

Certainly, it was the longest parade. The city’s traditional parade route runs from Bowling Green Park at the foot of Broadway to City Hall. The Apollo astronauts, however, after receiving the key to the city, continued up Broadway to Herald Square and then on to Times Square. As the New York Times noted, the confetti in Midtown was “made up more of paper towels and pages from telephone directories than tickertape” and that it grew “so dense that the astronauts could hardly see.”

As we write in Inside the Apple:

It was also one of the fastest ticker tape parades. The astronauts started at Bowling Green at 10:17 a.m. (about half an hour ahead of schedule) and arrived on the steps of City Hall just fourteen minutes later! Many people who showed up for the parade were disappointed to discover that the astronauts had already passed them by…. By 1:15 p.m. the astronauts were back at Kennedy airport to go to Chicago. They ended the day with festivities in Los Angeles. Having just been to the moon and back, a quick one-day jaunt across North America must not have seemed like such a big deal.

The astronauts had to go through customs upon their return--follow this link to see the astronauts declaration form ("Departure from: MOON. Arrival at: Honolulu, Hawaii, USA").

Read more about NYC history in

Friday, March 10, 2017

Postcard Thursday: The Great Theater Massacre of 1982

Yesterday, James had a piece in CurbedNY about the history of the Broadway theater district. The story focuses on five Broadway houses that were demolished in 1982 to make way for the Marriott Marquis Hotel, and wonders if that act of destruction was also part of what revitalized Times Square.

Read the story at http://ny.curbed.com/2017/3/9/14833004/broadway-theaters-closed-times-square-history.

* * * *

Read more about NYC history in

Thursday, April 7, 2016

Postcard Thursday: Longacre Square

If you had purchased this postcard exactly 112 years ago today, on April 7, 1904, you might have been doing so to commemorate the end of an era. For on April 8, the official name of the little triangle of land depicted here was changed from Longacre Square to Times Square.

As we write in Inside the Apple, at the time, the IRT was hard at work building the first subway line in the city. At the same time, the subway's main backer--financier August Belmont--was

lobbying his friend Adolph Ochs, the publisher of the New York Times, to relocate his paper’s headquarters to Longacre Square.

In theory, it was enough that the new subway connected the growing residential neighborhoods on the Upper West Side and Harlem to the city’s business district below City Hall. However, Belmont realized that to make the subway indispensable, he needed to develop real estate along the 42nd Street corridor as its own, independent business district. So, he turned to Ochs and encouraged him to consider building the Times a new all-in-one editorial and printing plant along the path of the IRT.

Ochs had purchased a controlling interest in the Times in 1896 and quickly boosted the paper’s circulation (by dropping the price to a penny) while raising the standard of its journalism. Belmont had long held a financial stake in the paper and saw the marriage of the newspaper and his new subway as a mutually beneficial enterprise....

To sweeten the deal, Belmont persuaded Mayor McClellan to rename Longacre Square after its new tenant. One of the Times’ chief rivals, James Gordon Bennett Jr.’s New York Herald, had moved to 34th Street in 1894 and their square soon became Herald Square. Belmont argued that the Times deserved the same courtesy; on April 8, 1904, Mayor McClellan presided over the opening of Times Square.The Times Building was the second-tallest skyscraper in the city in 1904 and the paper boasted that it could be seen from 12 miles away. This, of course, made it an ideal spot to shoot off New Year's Eve fireworks. Three years later, the fireworks were nixed in favor of the famous ball drop.

Of course, today Times Square is known for a lot more than just the newspaper (which is still headquartered in the neighborhood, but no longer on the square). Even when it was still Longacre Square, the area was already becoming the center of the city's theater district.

|

| The Olympia Theater (image courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York) |

Again, from Inside the Apple:

In 1895, Oscar Hammerstein opened the Olympia Theater on 45th Street, just around the corner from what was still called Longacre Square.... Though most theaters centered on Union and Madison Squares, the new Metropolitan Opera House had opened in 1883 at Broadway and 39th Street and a cluster of other theaters soon joined it. However, no one before Hammerstein wanted to build farther north. Longacre Square was known for livery stables and—much more important for theater-goers—its lack of electric lights, leading some to call it the “thieves’ lair.” Hammerstein, however, needed lots of space for his next venture, and land north of 42nd Street was cheap. The Olympia promised something for everyone: restaurants, opera, comedies—even a Turkish bath. Most of these features never came to fruition, but the theater itself was a success, proving that audiences would travel to 42nd Street to see a show.

In 1900, Hammerstein opened the Republic on 42nd Street. Three years later, the New Amsterdam had opened across the street, the Lyric a few doors down, and the Lyceum on 45th Street; by the end of the first decade of the 20th century, serious theater goers had abandoned Union Square and were happily coming to the new Broadway theater district. In 1902, the area received a new appellation, “The Great White Way.”(Why is it called "The Great White Way"? You'll have to read the book to find out.....)

* * * *

JOIN US AT THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY

On Thursday, April 21 at 6:30pm, we'll be at the Mid-Manhattan Library (455 Fifth Avenue, across the street from the main research branch) talking about Footprints in New York.We hope you can join us! Our illustrated lecture will look at some of our favorite stories from the book and highlight some of New York's most interesting characters, from Alexander Hamilton to Jane Jacobs to Edgar Allan Poe.

Copies of both Footprints in New York and Inside the Apple will be available for purchase and signing at the event.

Read more about the event on Facebook -- and follow us there if you haven't already: https://www.facebook.com/events/452455121618285/

****

Read more about NYC history in

Thursday, January 7, 2016

Postcard Thursday: Times Tower Redux

|

| (courtesy of the Library of Congress) |

Welcome to 2016! One of the things you'll notice with "Postcard Thursday" this year are more old photos, advertisements, etc. We'll still feature postcards from our collection, of course, but there such an abundance of good material out there -- why not share it all?

Last Thursday, we blogged about the Times Tower in Times Square and its role as the location of the annual ball drop on New Year's Eve.

|

| "The great white way" B'way south from 42nd St (courtesy of the Library of Congress) |

Today, we revisit the same building (pictured above before it had all the signage added to its facade). Did you know that the most expensive of those ads cost $4 million a year to rent? Even amortized over the billions of eyeballs that see them just on New Year's Eve alone, is it worth it?

* * * *

Read more about NYC history in

Available from your favorite online retailers (Amazon, Barnes and Noble, etc.) or from independent bookstores across the country.

Labels:

New Year's Eve,

TDK,

Times Square,

Times Tower,

Toshiba

Location:

Theater District, New York, NY, USA

Thursday, December 31, 2015

Postcard Thursday: Times Square, Western Union, and the Time Ball

Tonight, it is estimated that more than 1 billion people around the world will watch the illuminated ball drop in Times Square to ring in the new year. This New Year’s tradition in Times Square dates back to 1907—the dropping ball replaced an earlier fireworks display—but the notion of dropping a ball as a way of keeping time is a much older tradition.

In 1877, a ball was added to the top of the Western Union Building on Lower Broadway. (We couldn't find a postcard of this building in our collection; the above stereo slide from the Library of Congress will have to do.) Each day at noon, a telegraph signal from Western Union’s main office in Washington, DC, would trip a switch in New York and the ball would descend from the flagpole. Visible throughout the Financial District—and, more importantly, from all the ships in the harbor—it allowed people to reset their watches and ship chronometers. For the first time, New York ran on a standard time.

As the New York Times noted in 1877, this idea of a ball dropping to keep the time wasn’t new. For many years prior to the Civil War, the New York custom house had signaled the time with a ball drop, and in the 1870s it was common to find time balls in major European ports. However, when it began operation in April 1877, the Western Union ball was the only one in a North American port and quickly became a fixture of the Manhattan skyline.

|

| Telegraph wires run on Broadway outside the Western Union Building. After the Blizzard of 1888, these would all be buried underground. |

When the Times ushered in New Year's from their brand-new skyscraper in Times Square in 1904, they did so with fireworks shot from the building's rooftop. However, the police soon began to fear that fireworks might be a hazard in the rapidly developing neighborhood.

Instead, in 1907, the Times adopted the time ball as their symbol for ushering in the new year and placed a giant ball atop their skyscraper. That original Times Square ball, made of iron and wood and lit by 25 incandescent lights, weighed 700 pounds. We've been dropping a ball from the top of that building ever since. The current time ball, lit by energy-efficient LED diodes, now stays atop the old Times Building year round so that everyone who visits New York can see the actual ball that drops on New Year’s Eve.

Happy New Year everyone!

Thursday, July 23, 2015

Postcard Thursday: Paramount Building

If you stand in the middle of Times Square, you'll immediately notice two things: first, that's a lot of costumed Elmos in such a small space; and, second, one building isn't covered in brightly lit advertising: the Paramount Building.

That advertising is actually required by law:

There shall be a minimum of one illuminated sign with a surface area of not less than 1,000 square feet for each 50 linear feet, or part thereof, of street frontage.Somehow, the Paramount Building--perhaps due to its landmark status--circumvents the ordinance.

Built in 1926, the Paramount Building was the headquarters of the motion picture company of the same name. Designed by the firm of Rapp and Rapp, the building's pyramidal top was both a response to New York's restrictive 1915 step-back zoning law as well as an homage to the Paramount logo--a mountain topped with stars. In the new building, Rapp and Rapp placed that stars on the four-faced clock atop the tower.

Offices for Paramount were located on the upper stories of the building with a large movie house on the ground floor, designed to mimic the Paris Opera. Later, to boost revenues, Paramount added live shows, including the New Year's Eve 1942 appearance by Frank Sinatra that helped prove he was a superstar. Sinatra came on after Benny Goodman, and Goodman later recalled: “I introduced Sinatra and I thought the goddamned building was going to cave in. I never heard such a commotion with people running down to the stage, screaming and nearly knocking me off the ramp. All this for a fellow I never heard of.”

During World War II, the famous clock was painted black (as were many windows in midtown) to guard against Nazi bombing raids. The clock faces were not restored until 1996.

In 1953, crowds gathered at the Paramount to see the newest Vincent Price vehicle: House of Wax in brand-new 3D.

The theater finally closed in 1964; the space was later leased to the New York Times and today houses the Hard Rock Cafe. The building was landmarked in 1988.

* * * *

Explore more NYC history in

If you haven't had a chance to pick up a copy of Footprints yet,

Thursday, July 2, 2015

Postcard Thursday: Manhattan Sightseeing Cars and the Times Tower

Happy Actual Independence Day!

Today's postcard was mailed exactly ninety-seven years ago on July 2, 1908. It depicts what was then one of New York's most noted skyscrapers, the Times Tower, which had been erected a few years earlier in Times Square. Today, that building's been so altered that it is virtually unrecognizable, but billions of people around the world know it well: it's the spot where the ball drops on New Year's Eve. (You can just see the pole sticking out of the frame at the top of the image.)

This image, however, isn't about the Times Tower -- it shows the fleet of sightseeing cars that left from Times Square to take tourists around the city.

It's hard the read the reverse, but underneath the personal message, it offers an Uptown trip for $1 leaving four times a day or a Chinatown trip twice each evening for $2, including "all expenses." Chinatown tours became very popular at the turn of the 20th century, with visitors being taken to Chinese temples ("joss houses"), restaurants, and sometimes opium dens, almost all of which had been set up exclusively for the tourist trade. These tourist visits upset the police a great deal -- and all of New York's xenophobes, who were trying to force Chinese immigrants to go back to China. Two years later, the police summoned the five sightseeing companies that sold evening trips to Chinatown and told them to cut it out. As The New York Times reported, the police were attempting to make Chinatown a "clean colony," and the tourist excursions were sending the wrong signal. Moreover, the paper of record noted that "the Chinaman is a mysterious being, and there is no telling when he may start a rumpus."

To the best of our knowledge, any police admonition to the sightseeing companies was short lived, and Chinatown remained a key destination for out-of-towners, many of whom had probably never experienced Chinese cuisine or culture before.

This image, however, isn't about the Times Tower -- it shows the fleet of sightseeing cars that left from Times Square to take tourists around the city.

It's hard the read the reverse, but underneath the personal message, it offers an Uptown trip for $1 leaving four times a day or a Chinatown trip twice each evening for $2, including "all expenses." Chinatown tours became very popular at the turn of the 20th century, with visitors being taken to Chinese temples ("joss houses"), restaurants, and sometimes opium dens, almost all of which had been set up exclusively for the tourist trade. These tourist visits upset the police a great deal -- and all of New York's xenophobes, who were trying to force Chinese immigrants to go back to China. Two years later, the police summoned the five sightseeing companies that sold evening trips to Chinatown and told them to cut it out. As The New York Times reported, the police were attempting to make Chinatown a "clean colony," and the tourist excursions were sending the wrong signal. Moreover, the paper of record noted that "the Chinaman is a mysterious being, and there is no telling when he may start a rumpus."

To the best of our knowledge, any police admonition to the sightseeing companies was short lived, and Chinatown remained a key destination for out-of-towners, many of whom had probably never experienced Chinese cuisine or culture before.

* * * *

Explore more NYC history in

If you haven't had a chance to pick up a copy of Footprints yet,

you can order it from your favorite online retailers (Amazon, Barnes and Noble, etc.) or

from independent bookstores across the country.

you can order it from your favorite online retailers (Amazon, Barnes and Noble, etc.) or

from independent bookstores across the country.

And, of course, Inside the Apple is available at fine bookstores everywhere.

Tuesday, December 31, 2013

The Times Square Ball Drop

Tonight, an estimated billion people around the world will watch the illuminated ball drop in Times Square to ring in the new year. This New Year’s tradition dates back 106 years—the dropping ball replaced an earlier fireworks display—but the notion of dropping a ball as a way of keeping time is an older tradition.

Tonight, an estimated billion people around the world will watch the illuminated ball drop in Times Square to ring in the new year. This New Year’s tradition dates back 106 years—the dropping ball replaced an earlier fireworks display—but the notion of dropping a ball as a way of keeping time is an older tradition.

In 1877, a ball was added to the top of the Western Union Building on Lower Broadway. Each day at noon, a telegraph signal from Western Union’s main office in Washington, DC, would trip a switch in New York and the ball would descend from the flagpole. Visible throughout the Financial District—and, more importantly, from all the ships in the harbor—it allowed people to reset their watches and ship chronometers. For the first time, New York ran on a standard time.

As the New York Times noted in 1877, this idea of a ball dropping to keep the time wasn’t new. For many years prior to the Civil War, the New York custom house had signaled the time with a ball drop and in the 1870s it was common to find time balls in major European ports. However, when it began operation in April 1877, the Western Union ball was the only one in a North American port and quickly became a fixture of the Manhattan skyline.

(Western Union, afraid that it wasn’t always going to work, set up a system whereby a red flag would be flown from 12:01 to 12:10 p.m. on days that the ball refused to drop. Further, information would be sent to the press each day informing them whether the ball actually dropped at noon or had fallen at the wrong time!)

(Western Union, afraid that it wasn’t always going to work, set up a system whereby a red flag would be flown from 12:01 to 12:10 p.m. on days that the ball refused to drop. Further, information would be sent to the press each day informing them whether the ball actually dropped at noon or had fallen at the wrong time!)

In 1907, the New York Times—then owners of the skyscraper from which the ball drops on New Year’s Eve—adopted the time ball as their symbol for ushering in the new year. That original Times Square ball, made of iron and wood and lit by 25 incandescent lights, weighed 700 pounds!

In 1911, the original Western Union Building was demolished by the company’s new owners, AT&T, so they could erect a larger structure. (That impressive marble building, known as 195 Broadway, still stands.) Plans called for a new time ball, but by the time the new AT&T headquarters was finished, the ball had been replaced by a giant, gilded statue by Evelyn Beatrice Longman called The Genius of Electricity. (The statue remained on the building until 1980, when it was removed, restored, and installed in lobby of the AT&T headquarters in Midtown. It now resides in Dallas, Texas.)

The current time ball, lit by energy-efficient LED diodes, now stays atop the old Times Building year round so that everyone who visits New York can see the actual ball that drops on New Year’s Eve.

[This article was adopted from an earlier post from 2009.]

As the New York Times noted in 1877, this idea of a ball dropping to keep the time wasn’t new. For many years prior to the Civil War, the New York custom house had signaled the time with a ball drop and in the 1870s it was common to find time balls in major European ports. However, when it began operation in April 1877, the Western Union ball was the only one in a North American port and quickly became a fixture of the Manhattan skyline.

(Western Union, afraid that it wasn’t always going to work, set up a system whereby a red flag would be flown from 12:01 to 12:10 p.m. on days that the ball refused to drop. Further, information would be sent to the press each day informing them whether the ball actually dropped at noon or had fallen at the wrong time!)

(Western Union, afraid that it wasn’t always going to work, set up a system whereby a red flag would be flown from 12:01 to 12:10 p.m. on days that the ball refused to drop. Further, information would be sent to the press each day informing them whether the ball actually dropped at noon or had fallen at the wrong time!)In 1907, the New York Times—then owners of the skyscraper from which the ball drops on New Year’s Eve—adopted the time ball as their symbol for ushering in the new year. That original Times Square ball, made of iron and wood and lit by 25 incandescent lights, weighed 700 pounds!

In 1911, the original Western Union Building was demolished by the company’s new owners, AT&T, so they could erect a larger structure. (That impressive marble building, known as 195 Broadway, still stands.) Plans called for a new time ball, but by the time the new AT&T headquarters was finished, the ball had been replaced by a giant, gilded statue by Evelyn Beatrice Longman called The Genius of Electricity. (The statue remained on the building until 1980, when it was removed, restored, and installed in lobby of the AT&T headquarters in Midtown. It now resides in Dallas, Texas.)

The current time ball, lit by energy-efficient LED diodes, now stays atop the old Times Building year round so that everyone who visits New York can see the actual ball that drops on New Year’s Eve.

[This article was adopted from an earlier post from 2009.]

Labels:

Ball Drop,

New Year's Eve,

Times Square,

Western Union

Friday, May 18, 2012

News PAPER Spires at the Skyscraper Museum

At the end of the nineteenth century, when newspapers were at their peak, there were 43 daily papers in New York City. Most were published from "Newspaper Row"--the blocks of Park Row near City Hall--from grand skyscrapers that were among some of the first truly notable high-rise buildings in the city.

While most of these newspapers are gone and their headquarters have been torn down, the Skyscraper Museum has brought them back to life in their new exhibition "News PAPER Spires," running through July 15th. The small exhibition makes good use of archival drawings, blueprints, photographs, and newspapers themselves to tell the story of some of the city's most famous skyscrapers, including the World, Tribune, and Times buildings. (Of those three, only the Times building still stands--it's the building from which the ball drops on New Year's Eve.)

Of particular interest in Joseph Pulitzer's World tower, which was the first skyscraper to proclaim itself the tallest in the world. Designed by George B. Post (who also built the New York Stock Exchange and City College), the building reached to 309 feet to the top of the dome. It was a "giant among giants" to use the paper's PR terminology, and soon the Times and Tribune were racing to expand their buildings as they increased their circulation. Alas, the World tower came down when the approach ramps to the Brooklyn Bridge were expanded.

The show also focuses on the improvements in technology--from the use of rag paper to the invention of the linotype machine--that kept millions of papers circulating every day.

The Skyscraper Museum is located at 39 Battery Place (next to the Ritz Carlton) and is open Wednesday-Sunday, 12-6pm. If you can't make it in person, there's a virtual exhibition on the museum's website.

While most of these newspapers are gone and their headquarters have been torn down, the Skyscraper Museum has brought them back to life in their new exhibition "News PAPER Spires," running through July 15th. The small exhibition makes good use of archival drawings, blueprints, photographs, and newspapers themselves to tell the story of some of the city's most famous skyscrapers, including the World, Tribune, and Times buildings. (Of those three, only the Times building still stands--it's the building from which the ball drops on New Year's Eve.)

Of particular interest in Joseph Pulitzer's World tower, which was the first skyscraper to proclaim itself the tallest in the world. Designed by George B. Post (who also built the New York Stock Exchange and City College), the building reached to 309 feet to the top of the dome. It was a "giant among giants" to use the paper's PR terminology, and soon the Times and Tribune were racing to expand their buildings as they increased their circulation. Alas, the World tower came down when the approach ramps to the Brooklyn Bridge were expanded.

The show also focuses on the improvements in technology--from the use of rag paper to the invention of the linotype machine--that kept millions of papers circulating every day.

The Skyscraper Museum is located at 39 Battery Place (next to the Ritz Carlton) and is open Wednesday-Sunday, 12-6pm. If you can't make it in person, there's a virtual exhibition on the museum's website.

* * *

To read more about the race to build skyscrapers in New York

check out

To get RSS feeds from this blog, point your reader to this link.

Or, to subscribe via email, follow this link.

Also, you can now follow us on Twitter.

Thursday, January 19, 2012

Knickerbocker Hotel

The other day, the New York Post reported that work is finally underway on the old Knickerbocker Hotel on 42nd Street. According to the article, the Knickerbocker, which was turned into office space years ago, will once again become a luxury hotel.

The Knickerbocker was built by John Jacob Astor IV in 1906, and soon became a hot spot in the city. The bar, known as the Forty-Second Street Country Club, not only featured a free lunch, but also one of the most talked-about paintings in the city, Maxfield Parrish's Old King Cole. The massive mural depicts John Jacob Astor IV as Old King Cole. Taking a look at the painting, you can see that the king and his attendants are all making odd faces. According to lore, this is because Parrish was in a contest with other painters to see who could be the first to depict the act of someone passing gas. Evidently, Parrish won.

Also according to legend, the bartender at the Forty-Second Street Country Club, Martini di Arma di Taggia, invented the Martini at the Knickerbocker for John D. Rockefeller. When Rockefeller found the gin in the drink too harsh, he allegedly took an olive from a dish on the bar and plopped it in the drink. (In order for this story to be true, we must forget that the recipe for the martini prototype, the Martinez, was published in a bartender's guide twenty years before the hotel opened.)

The Knickerbocker was built by John Jacob Astor IV in 1906, and soon became a hot spot in the city. The bar, known as the Forty-Second Street Country Club, not only featured a free lunch, but also one of the most talked-about paintings in the city, Maxfield Parrish's Old King Cole. The massive mural depicts John Jacob Astor IV as Old King Cole. Taking a look at the painting, you can see that the king and his attendants are all making odd faces. According to lore, this is because Parrish was in a contest with other painters to see who could be the first to depict the act of someone passing gas. Evidently, Parrish won.

Also according to legend, the bartender at the Forty-Second Street Country Club, Martini di Arma di Taggia, invented the Martini at the Knickerbocker for John D. Rockefeller. When Rockefeller found the gin in the drink too harsh, he allegedly took an olive from a dish on the bar and plopped it in the drink. (In order for this story to be true, we must forget that the recipe for the martini prototype, the Martinez, was published in a bartender's guide twenty years before the hotel opened.)

The Knickerbocker opened just two years after the completion of the first line of the IRT subway, and as one of its amenities, there was a private entrance to the hotel from the 42nd Street subway station. This entrance is still there--if you go down to the shuttle stop--which is the only part of the Times Square station that is original--you'll see the sign for the Knickerbocker emblazoned above a door in the corner. You don't suppose they'll reopen this when the new hotel is finished, do you?

By the way, the Old King Cole mural left the Knickerbocker when the hotel was converted to offices, bouncing around New York until it found a home at the St. Regis, where it can be seen today.

* * * *

Read more about the birth of Times Square/42nd Street in

Friday, August 20, 2010

Around the World in 16-1/2 Minutes

Ninety-nine years ago today, the New York Times decided to find out how long it would take a commercial telegram to circle the globe. The record had been set in 1903, when President Roosevelt celebrated the completion of the Commercial Pacific Cable by sending the first round-the-world message in just 9 minutes. However, that message had been given priority status and the Times wanted to see how long a regular message would take -- and what route it would follow.

At 7:00 p.m. on August 20, 1911, the Times telegraph operator on the seventeenth floor of the newspaper's offices in Times Square sent a telegram that stated simply: "This message sent around the world." Sixteen-and-a-half minutes later, the same telegraph operator received his message back. In the intervening minutes the telegram had traveled from New York westward, stopping in:

Today, the building where the Times dispatched their record-setting message is called One Times Square and is best known for its news zipper and the dropping ball on New Year's Eve. The Times moved out in 1913 and eventually sold the building in 1961.

* * *

To get RSS feeds from this blog, point your reader to this link.

To subscribe via email, follow this link.

Or follow us on Twitter.

At 7:00 p.m. on August 20, 1911, the Times telegraph operator on the seventeenth floor of the newspaper's offices in Times Square sent a telegram that stated simply: "This message sent around the world." Sixteen-and-a-half minutes later, the same telegraph operator received his message back. In the intervening minutes the telegram had traveled from New York westward, stopping in:

- San Francisco

- Honolulu

- Midway Island

- Manila

- Hong Kong

- Saigon

- Singapore

- Madras

- Bombay

- Aden

- Suez

- Port Said

- Alexandria

- Malta

- Gibraltar

- Lisbon

- The Azores

- and then back to Times Square.

Today, the building where the Times dispatched their record-setting message is called One Times Square and is best known for its news zipper and the dropping ball on New Year's Eve. The Times moved out in 1913 and eventually sold the building in 1961.

Read more about One Times Square and the history of the area

in Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City.

in Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City.

To get RSS feeds from this blog, point your reader to this link.

To subscribe via email, follow this link.

Or follow us on Twitter.

Labels:

New York Times,

publicity,

stunts,

telegraphs,

Times Square

Monday, July 26, 2010

"Lights of New York" -- The First Real "Talkie"

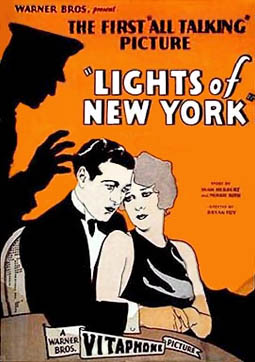

On July 26, 1928 -- eighty-two years ago today -- the first all-talking film, Lights of New York, opened across the country, ushering in the era of sound film and effectively killing the silent movie.*

The film had actually opened in New York at the Strand Theater** on July 6th to lukewarm critical reaction (The New York Times called it "crude in the extreme") but strong box office. Made for $23,000, the film ultimately grossed somewhere between $1.25 and $2 million dollars, thus proving that earlier sound films, like The Jazz Singer, weren't flukes. (Often billed as the first "talkie," The Jazz Singer has only two scenes of ad-libbed dialogue and the sound of Al Jolson singing; the rest of the film is essentially silent.)

The experimental nature of Lights of New York is apparent in its staging: boom mics were not in use, so stationery microphones were hidden throughout the set. The blocking in the film suffers, since characters could only speak when near a microphone, causing odd breaks in the dialogue as people walk from one microphone to another.

The film itself is a standard gangster movie: a rube from upstate comes to the city and ends up being the stooge for a Broadway speakeasy. However, the film had one notable line of dialogue: "Take him for a ride!" that went on to become a gangster cliche.

* By 1929, sound production was taking over and that year is

considered to be the last of the silent era though some directors -- notably

Charlie Chaplin -- would continue to make silent films well in the 1930s.

** The Strand is now gone; it stood on the site now occupied

by the Hershey's store at the northern end of Times Square.

by the Hershey's store at the northern end of Times Square.

To get RSS feeds from this blog, point your reader to this link.

To subscribe via email, follow this link.

Or follow us on Twitter.

Labels:

Lights of New York,

silent movies,

Strand Theater,

talkies,

Times Square

Friday, April 9, 2010

April 10, 1953: Vincent Price Ushers in the 3-D Craze in Times Square

With the success of James Cameron’s Avatar – and at least seventy 3-D films in the pipeline for release in the next few years – we may be entering a golden age of 3-D cinema. (And with ticket prices on Manhattan reaching $19.50 per person, cinemas are seeing the technology as their savior.)

Fifty-seven years ago tomorrow, on April 10, 1953, the Avatar of its generation – a horror film called House of Wax – premiered at the Paramount Theater in Times Square. The film boosted the career of Vincent Price, who would later go on to be known as the “King of Horror,” but who was known for a brief moment in the early 1950s as the “King of 3-D.”

However, what brought 3-D to the forefront was House of Wax, released the same weekend as Columbia pictures entry into the 3-D market, Man in the Dark. Considered one of the great horror films of its era, House of Wax not only took great advantage of the 3-D technology, but was also shown with stereoscopic sound – a rarity at the time. Thus, audiences at the Paramount would have been treated to both a feast for their eyes and ears.

* * *

* * *

Read more about Times Square as an entertainment mecca in

To get RSS feeds from this blog, point your reader to this link.

Or, to subscribe via email, follow this link.

Also, you can now follow us on Twitter.

But we’ve been here before and the last “golden age” of 3-D film may serve as a cautionary tale.

Fifty-seven years ago tomorrow, on April 10, 1953, the Avatar of its generation – a horror film called House of Wax – premiered at the Paramount Theater in Times Square. The film boosted the career of Vincent Price, who would later go on to be known as the “King of Horror,” but who was known for a brief moment in the early 1950s as the “King of 3-D.”

The technology to create 3-D films has existed since the birth of the medium in the late 19th century and there was a brief flirtation with making commercial 3-D films in the 1920s. However, the high costs of showing 3-D films, combined with the onset of the Depression, quashed the emerging technology. However, during the postwar television boom, Hollywood saw its revenues falling. This resulted in a wave of films marketed as “big screen” experiences and 3-D was resurrected as part of Hollywood’s arsenal for getting audiences back into the theater. The first 3-D film of this wave, released in 1952, was Bwana Devil, starring Robert Stack, and set in Africa (though clearly shot in the L.A. foothills).

However, what brought 3-D to the forefront was House of Wax, released the same weekend as Columbia pictures entry into the 3-D market, Man in the Dark. Considered one of the great horror films of its era, House of Wax not only took great advantage of the 3-D technology, but was also shown with stereoscopic sound – a rarity at the time. Thus, audiences at the Paramount would have been treated to both a feast for their eyes and ears.

Soon, Hollywood had dozens of 3-D films in production. In just the next 18 months, Price would star in Son of Sinbad, Dangerous Mission, and The Mad Magician. Other notable 3-D films released in 1953 and 1954 included It Came from Outer Space and the Cole Porter musical Kiss Me, Kate. By 1954, however, the shortcomings of the technology were becoming apparent. It was difficult for theaters to install and maintain the dual-projection equipment; audiences often complained about the red/blue glasses they were forced to wear (and the ensuing headache); and – Kiss Me, Kate notwithstanding – the quality of the films quickly plummeted with many just being gimmicky releases designed to cash in on the 3-D craze. By 1955, just two years after House of Wax’s opening, 3-D movies were for all intents dead and the idea would not be revived until the current wave of films.

* * *

The Paramount Theater still stands on Times Square, a magnificent reminder of that area’s former glory as a home to cinemas as well as Broadway houses. The Hard Rock currently occupies what was once the theater space.

* * *

If you happen to have a pair of red/blue 3-D glasses on a shelf somewhere, pull them out for this clip from House of Wax.

* * *

Read more about Times Square as an entertainment mecca in

To get RSS feeds from this blog, point your reader to this link.

Or, to subscribe via email, follow this link.

Also, you can now follow us on Twitter.

Labels:

3-D movies,

cinema,

House of Wax,

movies,

Paramount Theater,

Times Square,

Vincent Price

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)