Fifteen years on the Erie Canal

She's a good old worker and a good old pal

Fifteen years on the Erie Canal

We've hauled some barges in our day

Filled with lumber, coal, and hay

And every inch of the way we know

From Albany to Buffalo

-- From "Low Bridge Everybody Down" aka "Erie Canal"

|

| from the collection of the New-York Historical Society |

On October 26, 1825, one of the most important engineering feats of the 19th century was completed with the opening of the Erie Canal. A cannon was fired in Buffalo to mark the moment. Then, a series of cannons along the canal and the Hudson River had been set up for the occasion and as each gunner heard the shot, he fired his own; in 90 minutes the news passed, cannon to cannon, along the waterway to New York City.

Ten days later, New York's governor, DeWitt Clinton, stood on the deck of a packet boat anchored off Sandy Hook and poured a barrel of water from Lake Erie into the Atlantic Ocean. This "wedding of the waters," as it came to be known, was the symbolic completion of the Erie Canal, the most important waterway of its day and the engineering project that once and for all sealed New York's fate as the most important commercial city in America.

An entire chapter of Footprints in New York is dedicated to Governor (and NYC mayor) Clinton, the unsung hero of 19th-century New York politics. As we write in the book, Clinton

was the most important politician of his generation—perhaps the most important politician New York has ever had—which, considering the company, is quite an achievement.

Clinton was New York’s junior senator; then, he served ten one-year terms as the city’s mayor between 1803 and 1815. Later, as governor, he oversaw the building of the Erie Canal, the biggest engineering project of its day, which radically transformed New York’s economy. Had Clinton carried the state of Pennsylvania in the election of 1812—which he nearly did—he would have been president of the United States, and might have brought a quick resolution to the war with Great Britain.

Clinton’s influence is incalculable. From expanding trade through the Erie Canal to overseeing the real estate revolution embodied in the city’s rigid grid plan, the effects of Clinton’s years in politics are still felt today by every New Yorker.

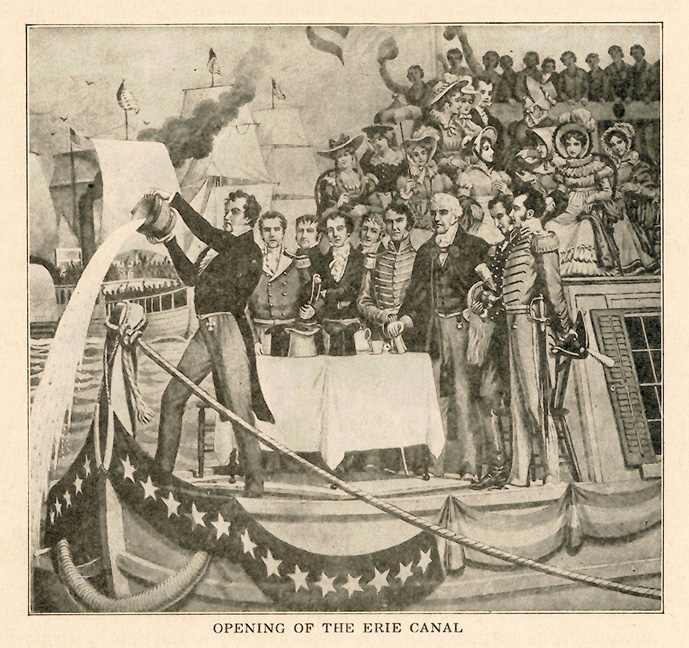

On November 4, 1825, in a ceremony for dignitaries and the press, Governor Clinton poured a small cask of water into the Atlantic Ocean. An artist captured the moment: Clinton stands on the edge of a barge, the miniature cask grasped in his hands, as the water—collected ten days earlier in Lake Erie—gracefully cascades into the sea.

* * *

.jpg)