Today marks the 40th anniversary of the inaugural running of the New York City Marathon. Now host to over 44,000 runners, the race is thought to be the largest spectator sport in the world, with over two million people lining the course. This is a far cry from the original race, run on September 13, 1970, which drew a field of just 127 people with the only spectators being family, friends, and bewildered passersby.

The race was organized by Fred Lebow and Vince Chiapetta and grew out of Lebow’s dissatisfaction with the Cherry Tree Marathon, run each February in the Bronx. The course had been picked due to the emptiness of Sedgwick Avenue, which the entrants ran up and down from Yankee Stadium for 26.2 miles. The Cherry Tree Marathon had about 200 entrants and there were no spectators, aid stations, or road closures; Lebow—who ran the race for the first time in 1970—thought he could do better by moving the marathon to Central Park. He convinced the Parks Department that he had the backing of anonymous “millionaire joggers” who would help produce the race. He also pointed out that from a practical point of view, the city would not have to deal with any traffic issues—earlier in the year, Mayor John Lindsay had closed Central Park to traffic on weekends.

The entry fee was one dollar; all the other expenses had to come out of Lebow’s and Chiapetta’s pockets as Lebow’s rich backers turned out to be a fiction. To save three cents per can, Lebow bought sodas in Greenwich Village and took them up to the park to use at the aid stations, but he forgot a can opener. Lebow and Chiapetta both competed in the race and when Lebow got too thirsty to continue, he tried to beg a soda from one of the park’s vendors since he had no money in his running shorts. A nearby visitor took pity on him and bought him a drink.

The race was organized by Fred Lebow and Vince Chiapetta and grew out of Lebow’s dissatisfaction with the Cherry Tree Marathon, run each February in the Bronx. The course had been picked due to the emptiness of Sedgwick Avenue, which the entrants ran up and down from Yankee Stadium for 26.2 miles. The Cherry Tree Marathon had about 200 entrants and there were no spectators, aid stations, or road closures; Lebow—who ran the race for the first time in 1970—thought he could do better by moving the marathon to Central Park. He convinced the Parks Department that he had the backing of anonymous “millionaire joggers” who would help produce the race. He also pointed out that from a practical point of view, the city would not have to deal with any traffic issues—earlier in the year, Mayor John Lindsay had closed Central Park to traffic on weekends.

The entry fee was one dollar; all the other expenses had to come out of Lebow’s and Chiapetta’s pockets as Lebow’s rich backers turned out to be a fiction. To save three cents per can, Lebow bought sodas in Greenwich Village and took them up to the park to use at the aid stations, but he forgot a can opener. Lebow and Chiapetta both competed in the race and when Lebow got too thirsty to continue, he tried to beg a soda from one of the park’s vendors since he had no money in his running shorts. A nearby visitor took pity on him and bought him a drink.

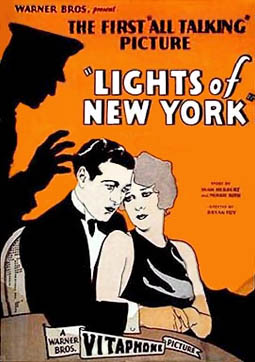

The winner of the race was firefighter Gary Muhrcke (pictured above), who had signed up that morning, with a time of 2:31:39. While two women had started the race, neither finished; indeed, more than half the field dropped out before the finish line. Muhrcke was awarded a $10 watch; other finishers received old bowling and baseball trophies.

* * *

Read more about Central Park in

To get RSS feeds from this blog, point your reader to this link.

Or, to subscribe via email, follow this link.

Also, you can now follow us on Twitter.