The modern holiday of Thanksgiving has become totally enmeshed with the story of the Pilgrims and

The Mayflower, though the feast held by those denizens of Plymouth, Massachusetts, was certainly not the first such commemoration in the New World. (Indeed, not only were there early thanksgivings, such as the one at

Berkeley Plantation in Virginia in 1619, but often these events were more somber and religious in nature than our current feasts.)

|

| Plymouth Rock |

However, the story of the Pilgrims and Thanksgiving is extremely relevant to the history of New York City, because Manhattan was their intended destination.

As we write in

Inside the Apple:

The Pilgrims’ voyage to the New World, which started out from the Dutch city of Leiden where they’d lived in exile, worried the fur traders. In the common Thanksgiving story, it’s usually left out that the Pilgrims weren’t en route to Massachusetts at all (which lay outside English territory) but instead had been granted the island at the northern limit of the Virginia colony: Manhattan. (Virginia’s claim to Manhattan was long-standing. When John Smith wrote to Henry Hudson about a Northwest Passage, it was because the river he was describing was part of Virginia.)

After a rocky start, where the Pilgrims were forced to abandon one of their two ships—perhaps because of sabotage by Dutch merchants—they continued on to the New World on the Mayflower, disembarking in Plymouth after a half-hearted attempt to sail further south. When it became clear that the English settlers were not going to move to Manhattan, Dutch traders hurriedly began staking a firmer claim to their territory.

By 1820 — the 200th anniversary of their arrival — the Pilgrims had long been an important part of the cultural DNA of New England, a section of the country that saw itself as separate from (and inherently better than) both the south and the Mid Atlantic states. As an anonymous contributor to the second volume of the

New England Quarterly wrote in 1802: “If the inhabitants of New-England are superior to the people of other countries, their superiority is to be attributed to their moral habits.”

In the 1740s, a 94-year-old man named Thomas Faunce had first identified Plymouth Rock as the spot where the Pilgrims had come ashore; on the eve of the Revolution, the boulder was dragged by a team of twenty oxen to Plymouth’s town square to be placed at the foot of a liberty pole. During the move the rock broke in two — a sign of America’s impending war with Britain, some thought — which only served to endow it with greater meaning.

* * *

Modern Thanksgiving didn't really get started until after the Civil War. James

wrote a history of that holiday for the Guardian in 2016:

|

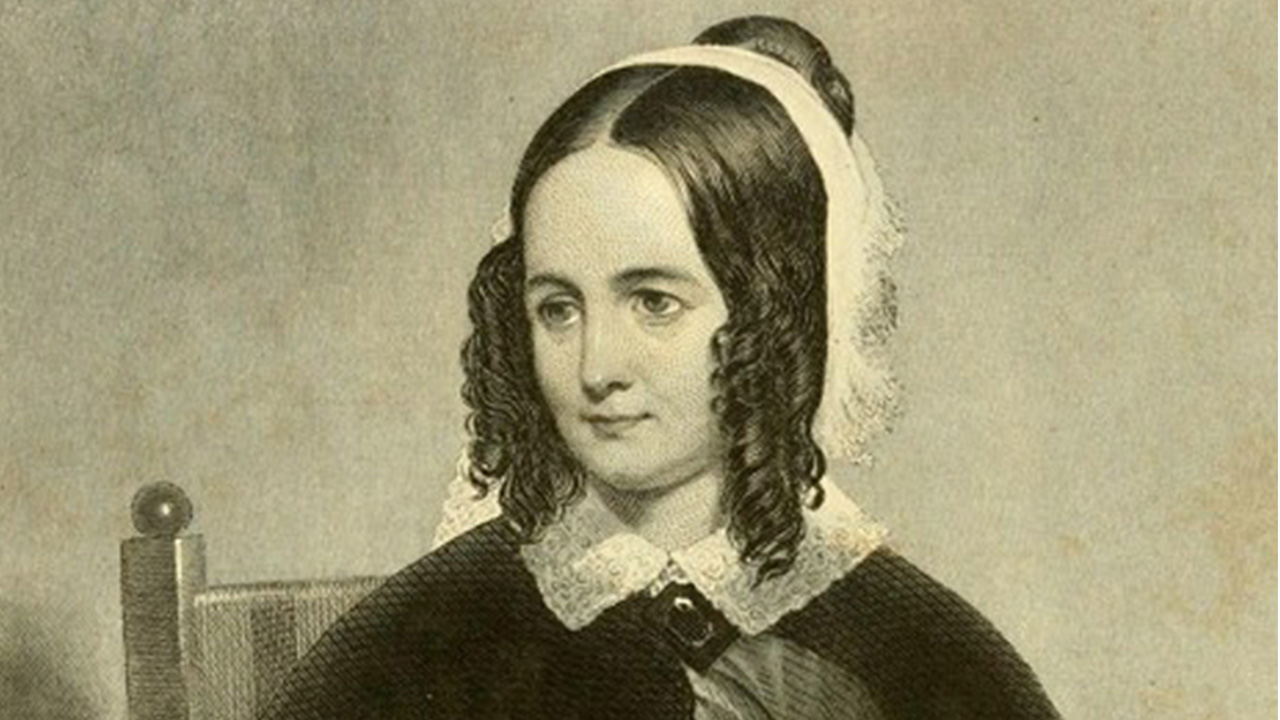

| Sarah Hale |

We owe our modern holiday to a writer named Sarah Josepha Hale, a magazine editor, novelist and poet (she penned “Mary Had a Little Lamb”).... In her first novel, 1827’s Northwood, Hale devoted multiple chapters to Thanksgiving; at one point, the character Squire opines that Thanksgiving will eventually be celebrated “on the same day, throughout all the states and territories” and “will be a grand spectacle of moral power and human happiness, such as the world has never yet witnessed."

[Hale] took over Godey’s Lady’s Book, which she grew into America’s most popular periodical. Though she insisted that Godey’s remain apolitical, each year Hale would advocate in the magazine’s pages for a New England-style Thanksgiving holiday to be “celebrated throughout the whole country on the same day”. She also wrote to every state governor each year asking that a Thursday in November (sometimes the third, often the last) be dedicated to Thanksgiving.

Many southern politicians were less than enthused. Governor Henry Wise of Virginia wrote back in 1856 that the “theatrical national claptrap of Thanksgiving” was merely a mask to aid “other causes”. By other causes, Wise meant abolition. He knew Thanksgiving was a Trojan horse; cranberry sauce and pumpkin pie would get the northerners through the front door, and they’d soon be spreading their “claptrap” throughout the slaveholding south.

That same year, the Evening Star in Washington DC, along with other southern newspapers, complained that Thanksgiving was an attempt to replace the “legitimate Christian holiday” of Christmas with a secular day where “an astonishing quantity of execrable liquor will be guzzled”.

Still, by 1863, Hale had convinced Abraham Lincoln to declare a Day of National Thanksgiving, though it would not become a true national holiday until Franklin D Roosevelt signed it into law in 1941.

* * *

Abraham Lincoln actually declared Thanksgiving Day

twice.

In the words of the original proclamation, issued in October 1863 and actually written by

Secretary of State William Seward, the former senator from and governor of New York:

I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens. And I recommend to them that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to his tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility and Union.

However, this was actually Lincoln's second Thanksgiving proclamation of the year. On July 16, he had issued the following proclamation (again, likely by Seward):

Now, therefore, be it known that I do set apart Thursday, the sixth day of August next, to be observed as a day for National Thanksgiving, praise and prayer, and I invite the people of the United States to assemble on that occasion in their customary places of worship, and in the form approved by their own conscience, render the homage due to the Divine Majesty for the wonderful things He has done in the Nation's behalf, and invoke the influence of His Holy Spirit, to subdue the anger which has produced, and so long sustained a needless and cruel rebellion; to change the hearts of the insurgents; to guide the counsels of the Government with wisdom adequate to so great a National emergency, and to visit with tender care, and consolation throughout the length and breadth of our land, all those who, through the vicissitudes of marches, voyages, battles and sieges, have been brought to suffer in mind, body or estate, and finally to lead the whole nation through paths of repentance and submission to the Divine will, back to the perfect enjoyment of union and fraternal peace.

(FYI: That's

one sentence.)

The first Thanksgiving of 1863, August 6, was celebrated with proper solemnity. As the

New York Times noted the next day, "The National Thanksgiving was observed throughout the City yesterday by an almost entire abstaining from secular pursuits. The stores throughout were closed, and there appeared to be a very general desire to unite in the purposes of the day -- Thanksgiving and Praise. Very many of the churches were open, where proper observances were had, and each was crowded to overflowing." What they were praising and/or hoping for was continued Union success; with the Union victory at Gettysburg in July, many hoped that tide of the war had finally turned in favor of the North.

Of course, on the minds of New Yorkers would have been the fighting closer to home -- the

Civil War draft riots -- which had waged on the streets less than a month earlier. However, it is unclear if the riots played any role in the Thanksgiving commemorations.

Having celebrated Thanksgiving in August, why did Lincoln then proclaim another one in November? The declaration for this second Thanksgiving seems little different from the first; there had been no major Union victories in the meantime for which the nation could express thanks; and Lincoln's proclamation doesn't make any ties to harvest festivals, the Pilgrims, or any of the things we now firmly associate with the holiday.

* * *

Happy Thanksgiving! If you are looking for a great gifts this holiday season,

Inside the Apple and Footprints in New York look great on anyone's shelves!

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/48909907/hanshaackeledeimage.0.0.jpg)